It is a strange thing to miss your own father’s funeral.

Today is the second anniversary of my father’s death. He passed away while my family and I were in transit to visit family in Sweden. Mom waited until we had completed our first flight and were about to board our trans-Atlantic flight before telling me that Dad was nearing the end. Mom knew I would have stayed, had I known, and she wanted us to enjoy our trip. Dad would have wanted the same.

In addition to being out of the country, it was also 2020. Covid. Funerals weren’t really happening.

My Mom, my brother Matt, as well as close family & friends held a small, almost-impromptu graveside service where my brother read excerpts from the eulogy I wrote (posted below). Because Dad had Alzheimer’s, his passing was not a complete surprise. His slow slippage provided considerable notice to think about Dad and to write his eulogy, which I worked on intermittently for perhaps three years prior.

Although seven time zones ahead, I paused at the time of the funeral, to think about Dad, about Mom, Matt, those attending, and the impact on my own kids, having officially lost a grandfather – though, to them, he was lost before that.

I debated if I should post this because it is very personal, and a blog seemed a trite place to house this text. Now, two years hence, I concluded it would be as appropriate as the local newspaper, an ephemeral, yet standard placeholder for such things.

So, here it is…

My Father’s Eulogy

Dad used to complain in private when ceremonies lasted too long, especially weddings and funerals. These were the worst culprits in his view. This written eulogy, a virtual funeral of sorts, is already approaching the upper limit of Dad’s tastes.

Dad’s idea of a good funeral was a single speaker with this poetic message,

“He was here for a while. He lived a good life. We loved him. We remember him and his impact on our lives. Now he’s gone. Let’s all head over to the buffet and eat. There’s a big dessert table.”

I think that’s a decent summary of his view on the topic. Unfortunately, I’d like to say a bit more than that. Apologies to Dad in advance, but here we go.

Knowing Dad

Few people would know what Dad thought about a given topic,1 but you could know how he thought about it. Dad was talented at articulating his thought processes and logical frameworks of thinking.

Even fewer would know how Dad felt, that is, his emotions. On a personality spectrum, ranging from emotional to analytical, Dad leaned toward Spock (from Star Trek). He was hyper-logical and extremely analytical. Dad also had exceptional emotional control, always defaulting to reason.

Because of this, no one really knew Dad fully, except perhaps Mom. Their lifelong bond was unmistakable, unusually deep and transparent. And no one knew him in the way his boys (Matt and I) knew him. He was different with us. Different in all the best ways.

Although Dad was Spock-like publicly, it might surprise you to learn, with his boys, he could be visibly emotional and very tender-hearted, never shy to say “I love you” or “I’m proud of you”… or to cry.

Dad’s eyes would water when he spoke about emotional topics. He once told me his father was the same… and I share some of that trait as well. He was so confident and transparent; he didn’t care if it showed. But only to his immediate family, as far as I know.

One day in the car, driving home from Elgin, we were talking about people, family and emotions when Dad said, “Emotions are difficult to discuss. Look, my eyes are watering right now just talking about it.” He looked over to show me his glossy eyes. It was a lesson for his son… less so about the content of the conversation, but more about allowing yourself to be vulnerable, especially with those you love. Dad taught me that day, perhaps unwittingly, that vulnerability is a prerequisite for the depths of love. He should have also kept his eyes on the road while driving, but that’s not the point here.

On Discipline

Dad commanded respect with an unmistakable presence when he entered a room. There was no question about his authority. He exuded it. As an adult, I learned many of my cousins were afraid of their Uncle Dick when they were kids. They thought he was extremely strict, which was odd to me, because I didn’t think of him as strict at all growing up. Looking back, I can see their viewpoint, but as kids, “normal” is however you are raised.

Dad might have been strict, but he was fair. This is an important point. If you knew the rules – and they were few and quite reasonable – and stayed within those bounds, there was no strictness to be found. When we did cross those boundaries, as is inevitably the case (how else could we know the boundaries were real?), Dad was fair and characteristically unemotional in his response. In these cases, we generally knew what to expect. There would be a short discussion comparing the specific behavior relative to expectations. Dad would spend time to understand what drove our wayward behavior. The “why we did it” was important to him. He also ensured we fully understood why the specific behavior was unacceptable, as it related to more fundamental principles. He then took time to explain the consequences and why they were necessary. By this point, as a kid, you just wanted it over with. Less explaining. More finality. However, looking back, almost without exception, the consequences were relatively small and proportional to the offense. Seemed fair to me, even as a kid, and especially as an adult.

One of the greatest gifts Dad gave to his boys, besides care, provision, and stability, was love demonstrated through consistent discipline (never punishment).2 This cemented the idea there are consequences to actions (good and bad). Dad understood the assignment of seemingly random, unrelated consequences to our errant actions would associate within us a distaste for irreverent behaviors, thus saving us much pain later. Dad understood the minor discomfort of carefully measured parental discipline for our trivial youthful infractions would pale in comparison to the consequences the harsher world would dish out upon those who make larger mistakes later in life precisely because they were not taught the distaste for negative consequences for misbehaviors while still young. In other words, Dad’s implementation of the disciplinary process was a model for good parenting.

Leadership

Dad was the guy you could count on. Consistent. Dependable. Always fair. This made him successful in his career and a great manager. At work, his team respected him, his leadership, his competence, and unquestionable professionalism.

Growing up, I remember attending quite a few of the large annual company picnics, sponsored by Dad’s employer. There were often silly games, all in good fun, normally at the boss’s expense. One year it occurred to me, the reason Dad was normally one of the 3 or 4 people who had to play these pie-in-the-face kind of games was because he was, in fact, the boss.

He was a leader. For him, it was instinctive. He grew up in a military household and perhaps this helped shape his personality… that of a General.

I was always proud of my dad. Partly for his career success (most of us know he retired when he was 50. That’s on the early side for most people, but he worked hard and was not a consumer), but mostly, I respected Dad because he was willing to:

1) stand up for what was right;

2) take the high road in his decisions, even at personal cost. For Dad, decisions came easily when it came to ethics; and

3) admit when he was wrong.

A little more on these points…

Standing Up for What’s Right

An incident happened in a parking lot when my brother Matt and I were young teenagers. I wasn’t there, but I heard about it later that evening. Matt was there so he could better tell this story. As I recall, Matt and Dad were walking down a sidewalk in town and came across a man squabbling with a lady. Apparently, it was getting heated to the point it appeared physically threatening to the lady. Dad stepped in and told the guy, a complete stranger, to leave her alone.

Matt thought they were going to fight. Evidently, it got close enough that Dad had raised his fists, ready to brawl. The other guy backed down. So, Dad grabbed a small spiral notepad and a pencil (which he often carried with him), calmly walked to the guy’s car, and wrote down the license plate number. The guy walked up and ripped the paper from Dad’s hands, to which Dad replied factually, “That’s OK, I have it memorized.”

Sounds about right. Cool and collected in the face of uncertainty. Spock with a strong moral compass.

While we are on this topic… I never saw Dad lose his cool.3 He told me on several occasions, “The first person to lose their cool in an argument loses. The angrier, louder person may think he won the argument, but everyone watching thinks the opposite.” Dad lived by this keep-your-cool principal.

There’s another well-known story about Dad not losing his cool in the face of significant interpersonal conflict at a public gathering. The incident happened at the MUD board meeting when Mom and Dad lived in Houston… but I think many of you already know this story. If not, ask me and I’ll tell it.

The point here is, my Dad was cool under pressure and consistently stood up for what was right… simply because it was the right thing to do.

Ethics

Dad was ethical in his dealings with people.

Sometime around my high school years, Dad had rented a piece of equipment from Home Depot. When we returned it (I went with him), the guy at the counter forgot to charge us. The cashier had closed the ticket and the clerk had shelved the equipment, but Dad couldn’t let it go. He mentioned to the clerk that they forgot to take our money.

The young clerk replied jokingly, “Well, I’ve closed out the transaction, so we’re good, but, I mean, I can still charge you if you want.”

Dad replied, “Well, I used the equipment so I guess you should charge me.”

And he did, slightly baffled, “That will be $49 sir.”

Dad pulled out his wallet and handed the clerk some cash, as if the previous two minutes never occurred. To Dad, this was just logical… and right.

Kids learn from our actions more than our words. That day, I learned more than a $49 lesson (or whatever the equipment cost). I learned that character matters. For me, that was perhaps the best $49 Dad ever spent.

Some 20 years later, at another Home Depot, the same thing happened to me. I had rented a piece of equipment. Upon returning it, they forgot to charge me (what are the odds?). I’m not sure how those guys stay in business now I think about it. Anyway, in that moment, I remembered my Dad and what he had done in this same situation. The script was almost identical. And, like my Dad 20 years before, I asked the clerk to charge me. Unfortunately for me, nobody was there to absorb this lesson.

So, while Dad’s character was amplified through this experience, my character was just out $50 bucks. Kids, pretend you were witnesses and imagine you also learned the same lesson.

That was just one example to illustrate the consistency in which Dad would do the right thing. It was just in his nature, the core of his constitution.

Speaking of doing the right thing and of “being right”…

On Being Wrong

Dad, like all of us, could also be wrong. Most of us, when we are wrong, defend our position, no matter how dumb it is, even after we realize it’s dumb. But when Dad realized he was wrong, he reflected on it, and could change his view.4 He learned from being wrong. He was always learning. In fact, if you differed in opinion, and got tired of arguing your viewpoint, Dad would say, “Don’t give up so easily, keep arguing with me.” He was learning… and teaching… and forcing us to learn how to formulate coherent arguments. For this, he was an excellent teacher.

For a long time, Dad carried a scrap of paper in his wallet (probably from that same small spiral notebook, which he called his “external brain”).5

Anyway, this scrap of paper showed his calculation of how far a 6-foot person could see across the horizon before the curvature of the earth forced his vision to fall off into space. Why did he keep that? He had done this calculation before as a younger man and thought he had remembered the answer. Then, one day, I believe he and Matt worked it out again on this scrap of paper (at Grandma and Grandpa’s kitchen table in Elgin)… but the answer was different from what Dad had remembered. He kept this scrap of paper in his wallet as a continual reminder that he was (and, by extrapolation, all of us are) fallible. He understood he could be wrong. Dad had an extreme sense of objectivity.

Friends

To my knowledge, Dad had no friends outside of the extended family (except for his college roommate Tony, who I believe he saw maybe just a few times after college). Strangely, I’m not sure Dad needed friends and normal socialization. He lived his life for his family and that was enough for him. And for that, I am a benefactor and appreciative of his on-going service to grow Matt and I into respectable men (well, at least Matt).

Dad was a provider. Financially and emotionally. He gave stability to our youth, loved us, and took time to mold our characters. What more could you ask from a father?

What He Lacked

If everyone were perfect, without differentiating imperfections, what would there be to love? We love people not despite their flaws, but because of them. Fortunately for us, nobody is perfect.

Dad was no exception.

There were a few areas where Dad was not known to excel. Notably, four things come to mind:

- Generosity & philanthropy

- Patience (except for teaching)

- Exploration, adventure and an appetite for risk

- Sense of humor6

Fortunately, Mom embodied these very attributes. It was the perfect blend of parenting, for which I am forever grateful.

Much to our added benefit, Matt and I were also surrounded by other adult men who perfectly complemented and supplemented these attributes – our uncles.

Generosity

Uncle Bub would give the shirt off his back to a perfect stranger. In Bub’s world view, if someone needed help, you helped them, without question. Dad used to marvel that Bub would loan some random guy walking up from the turnpike a tool or a spare tire from his garage. This is generosity in practice and a great attribute to be modeled. And, Uncle Bub, it did not go unnoticed.

Patience

Uncle Donald was the epitome of gentleness and patience. It was primarily how he was known. When I spent time with Donald, I knew he cared, about me. To know Donald, was to understand what it means to be patient and kind to others.

Adventure

Uncle Phil didn’t mind a little risk. He went out and explored and made his life interesting, often on a sailboat. For me, Phil was a great example of calculated risk taking, adventure and entrepreneurship. Much of my thinking is modeled after my Uncle Phil, who taught by example, how to appreciate points-of-view different from your own. He was often more curious about what someone else thought about a topic (even young people), than trying to convince you of what he thought. A model conversation with Phil starts with, “So, Andy, what do you think about…”

My Uncle Monty, perhaps the most unique person I know, also showed us a carefree sense of adventure in life, and an appetite for risk in pretty much everything he did.

Humor

While Uncle David provided an example of entrepreneurship, work ethic, a strong sense of building community and helping others (collectively and individually), he also showed it’s OK to loosen up and have fun. In this great, yet beautiful tragedy of life, there can also be fun.

Uncle David has a wonderful sense of humor through storytelling and continually keeps people laughing. I know every day must not have been fun for Uncle David, but he made every day around him fun for the rest of us. And yet, it wasn’t only surface level fun. Uncle David also balanced humor and wit with heartfelt depth in conversation.

The point here is that where Dad lacked, there were supporting characters to round out the cast. And, Mom and Dad ensured we had time with them. That was also a gift.

In Closing

Dad, this is longer than you would have wanted so I’ll end with this.

You were a great Dad.7 You were here for a while. You lived a good life. Thank you for making my childhood so wonderful. You made us feel loved, and we loved you. Now you’re gone. Let’s go eat… and at Christmas, someone please save an honorary slice of pecan pie for Dad.

Update (April 2024)

I was visiting my mom at her house in Oklahoma this past week, nearly four years after my father passed. On her office desk, mom had found a letter my cousin Paul wrote to me, a response to the eulogy I wrote for my father’s funeral. Apparently, in the fog of the season, mom didn’t read it, nor did she pass it along to me. Consequently, Paul’s letter was four years delayed in its delivery. I read it for the first time last week.

I liked it so much, I have posted it here as a follow-up to what is written above. What follows is the letter from cousin Paul to cousin Andy.

***** LETTER FROM PAUL *****

Cousin Andy,

I put together a few stories of my own. I hope you enjoy them.

RISK

I’ve shared this story before. It’s one of my all time favorites.

In the 1970s, NASA launched Voyager 1 and 2. The mission was to explore deep space. The launch occurred when I was a baby. By the time my sister was in college, we were exploring Neptune. That’s about the time this story picks up… circa ‘89. By this point, both spacecrafts were adrift in deep space, and, importantly, both were carrying shiny disks with road maps to earth. How far could they go? Who would we find? What would the aliens be like? Everyone on “the hill” was marveling at mankind’s achievement (count me in that group). Uncle Dick sat there quietly, taking it all in, but with this look:

When the discussion was almost over, your dad posed a simple question (paraphrasing): “Has anyone considered the possibility that what we’ve done is not a good idea?” Now that I think more on it, I’m pretty sure that’s an exact quote. Maybe not. Regardless, I remember what followed — dead silence. It was classic Dick Jones. Listen. Analyze. Say something mind-boggling. (And of course identify risk along the way.)

(Aside: I learned that a plainly worded rhetorical question is a good way to make a point.)

OPINIONS

It is true that your dad rarely voiced an opinion. Likewise, he rarely acted impulsively. For Dick Jones, facts mattered more than opinions. But, on January 11, 2014, he let his guard down. The best way to conceptualize what happened that day is to simply share what your dad saw. Turns out, I can do that. Check out the five-year-old pallbearer below.

After the funeral, Uncle Dick walked straight to me. He asked a pointed question. He wanted to know why I brought a child to a funeral. I gave a pointed response: “because kids are not exposed to death and I think that’s wrong” (conveyed in somewhat of a defensive tone). Your dad did one of these looks:

Uncle Dick agreed. In fact, he made it a point to say how much he respected my decision. What he said to me that day remains one of my most cherished moments as a parent. It may not sound like that big of a deal, but Dick Jones acted on impulse that day and shared his opinion. Fascinating…

(Quick side note: your dad shared opinions with me on other occasions, too, but mostly through private email. From time to time, we talked about constitutional issues and the role and importance of America’s jury system. I enjoyed those discussions immensely).

EXPLORATION AND ADVENTURE

We will have to agree to disagree on this one. Your dad was definitely adventurous. From my perspective, he was Paul Bunyon-like. He was tall and strong. To boot, the man knew everything (and if he didn’t know something, he would figure it out). There are many forms of adventure and Dick Jones was not afraid to venture out in his own way. If memory serves me correctly, he once obtained a pesticide certification so he could treat his own termites or something like that. He tinkered with things constantly. He repaired almost anything… and likely broke almost anything. I admired his courage and adventurous spirit in those respects.

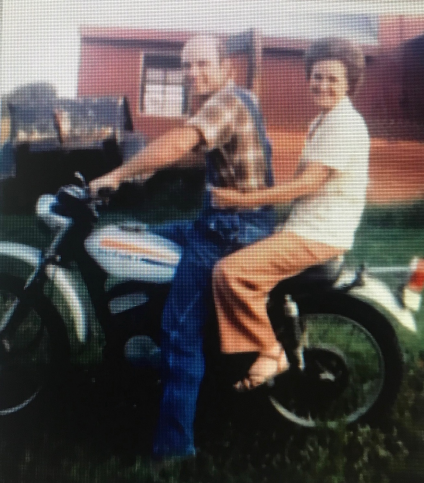

The Paul Bunyan I knew was also an explorer. He lived on a gigantic farm with a wild Clydesdale (Wendy),8 domesticated bees (not to mention hornets that most certainly were NOT domesticated), and scores of cool things — canoes, motorcycles, tractors, fireworks, and even fences that would shock the piss out of you (literally and figuratively).9 Everyone made the pilgrimage to “Dick and Judy’s farm,” including Grandma and Grandpa (who would only travel to California and Ft. Cobb, and only then with a year of advance planning). The farm was the epicenter of adventure and exploration. And, once there, Uncle Dick was the adventure-Chief. Here is proof:

You tell me, but I’m pretty sure that’s GRANDMA on the back of a dirt bike?? I rest my case.

PATIENCE AND GENEROSITY

This is getting way too long… one more quick story and I promise this will be done. Andy, you were not the only one who grew up with a generous uncle. My Uncle Dick was always there to lend a helping hand. He’d wash dishes, carve a turkey, setup tables/chairs, crank an ice cream handle, etc. He was pretty handy, too.

Another example of generosity, one that is more personal to me, comes to mind. Your dad took me sailing once. For some odd reason, I can still remember that day like a video. It didn’t last long, and the boat wasn’t very big. But the gesture resonated to me, even back then. Your dad took the time and effort to share a unique experience with me. I didn’t realize it at the time, but I “logged” a memory that day. To this day, I “pay it forward” each time I take a kid out on the boat with me.

THIS IS FINALLY DONE…

I read Mark Taylor’s email. He said: “I feel so lucky to have known ‘Uncle Dick’ at his best.” He added: “The times we spent at the farm live on in me to this day.” Well said, Mark. I agree wholeheartedly.

Please accept my heartfelt condolences for your loss.

My Father Knew He was Fallible

Follow Past Midway if you would like an email notification of new posts.

FOOTNOTES:

- Dad was guarded in revealing his opinions, except when they were about the appropriate duration of weddings and funerals.

- Punishment is reactionary and strives to inflict discomfort on someone, a sort of tit-for-tat exchange. Discipline is the assignment of the minimal unpleasant outcome required for a child to associate a negative consequence for that specific behavior and for behaviors like it. Disciplines teaches. Punishment just hurts.

- One notable exception. Dad would lose his cool when he banged his head on something. He assured me it hurts more when you have less hair. I better understand that now.

- To be clear, it took some bulldog concerted energy for this to happen.

- When I was young, I couldn’t understand how a part of Dad’s brain could be outside of his head. So confusing.

- A small notable exception comes to mind. In first grade, we had to get a parent’s signature on our homework assignment. Dad signed my paper as “Dad Jones”, in basic print. He thought this was hilarious.

- Before Dad’s memory failed him, I told him this in person. He cried. That was all I needed to tell my Dad as we said goodbye that day. We were leaving to go back home… and so was he, slowly.

- I’ve heard people whispering and giggling when I refer to Wendy as a Clydesdale. Like I told your mother, it’s my story. It is my memory and we’re not going to change this part.

- Notably, taking a wiz on an electrical fence is ill-advised.

Perfectly said. And, while dad would not want the accolades (mostly), he would be so very proud of the son he raised who could voice them so well.

Very good Andy! Nice way to remember a sad day. I was impressed the the first time I read your notes about your dad but the older I get the more I appreciate them.

A beautiful tribute by a loving son.

Top work, Andy. Your dad was an awesome guy.

And thank you for the kind words about my dad. I miss him and mom every day.

This is so beautiful and it really touched me. The world lost a good man and an amazing father. Thank you for sharing your dad with us.

This is such a beautiful tribute to the man that was your father. I met your father after your parents moved to Elgin. Matt did an excellent job of sharing your words at the funeral. It was a short lovely service your Dad would have loved it!