Numerous threats encompass a nation and a national psyche – some real, some existential, some external, some internal. In this post, I discuss a real internal threat, one of our own creation, completely under our control, but not under control – our national debt.

Our nation’s enormous debt and persistent deficit spending significantly constrain our future economic options and form the basis for any reasonable economic thesis.

If thousands of factors drive an economic model, for the U.S., there’s the potential for war, the debt, and then everything else.

The Congressional Budget Office creatively refers to the national debt as “a daunting budgetary situation”. This is understated.

Our debt is so massive, it adds considerable fragility to the longevity of the Republic.

Background

In 2019, pre-Covid, I wrote an article titled, Tariffs, Debt, Social Security & The Fed – An Economic Theory, where I argued the following events would unfold:

- An event, originating in China, could trigger a domino effect whereby China would have less economic output and therefore a lower trade surplus with the U.S. This would lower demand for U.S. Treasuries, thereby increasing interest rates.

- Social Security, concluding its final surplus year in 2019, would further reduce demand for U.S. Treasuries, also edging interest rates higher.

- An increase in interest rates would require a greater percentage of our tax revenue just to service our debt.

- The confluence of these economic pressures would lead to significant inflation and potentially a recession.

This path, except for the presupposition of a global event like Covid, seems obvious in hindsight. But in 2019, the market was seemingly doing well, employment was low, salaries were solid, and inflation was negligible (and had been for years). At veneer depth, the economy felt healthy, even robust. But I scratched below the surface, formed an economic thesis, and wrote about my concern.1

The point of recapping my 2019 article is to provide some historical context for what I discuss in this blog post and to self-aggrandize, because, let’s face it, I have so few opportunities for that.

What I missed in my 2019 thesis was the Fed’s enormous intervention. I didn’t see that coming, at least not on the scale implemented. More importantly, I missed a key concept I now better understand – the Fed’s fundamental proclivity for an upward market bias.2

Anyway, if that was my economic thesis in 2019 (and it was), this is my updated thinking, which is a continuation from the previous views, coupled with five more years of events and data since. Obviously, this is just my interpretation of the current economic data. Reality could (and likely will) unfold quite differently.

The future has a certain knack for unpredictability.

The Debt Problem

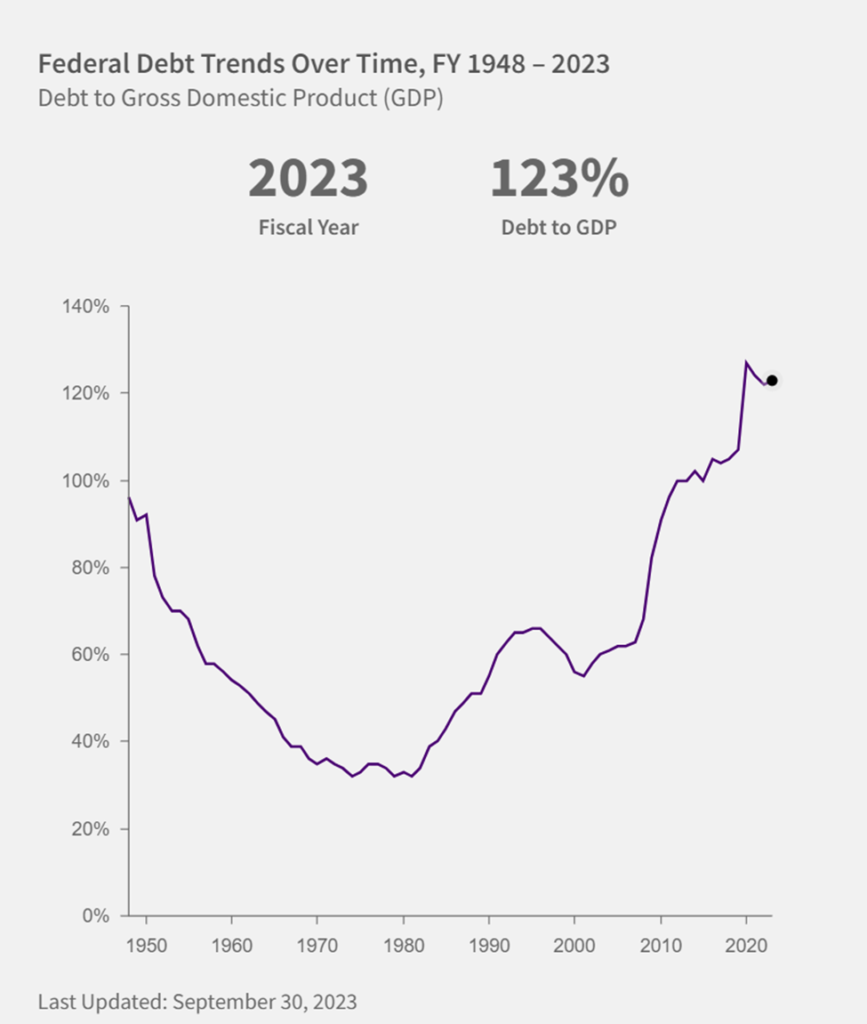

- Our national debt, at 123% of GDP (2023), surpassed any reasonable level years ago, as measured by the risk of our ability to service it.3

- If we compare this debt-to-GDP level to other countries, there are only a few countries worse off: Italy, Singapore, Greece, Venezuela, Sudan, Eritrea, and Japan.4

- We continue to add debt through annual deficit spending, as if there’s no ceiling.

Conclusion: The U.S. debt vector is unsustainable.

If you look at the far-right side of the chart above and think, “Well, it looks like the debt is going down… at least a little.”

It’s not.

The debt (the numerator in this ratio) went up. The economy (the denominator) also went up. The economic growth outpaced the debt increase, bringing the ratio down. The recent, excessive spike in this chart was a down economy during Covid. The money printing during Covid stimulated the economy. Hence the recent dip.

Interest Expense

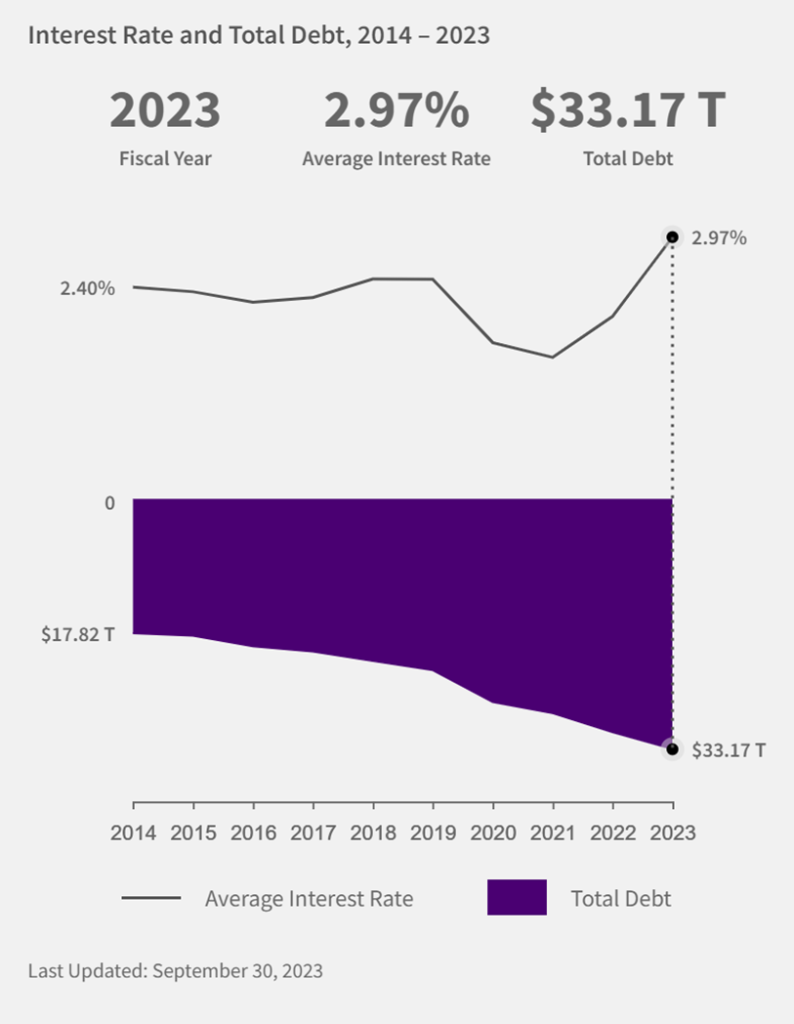

The problem with excessive debt is the required interest payments. Higher debt requires more of our tax revenue to pay for the interest expense. This leaves less money to fund government spending, including promised entitlements.

Further, as The Fed has raised rates, not only is the debt load greater, but the interest rate on that debt is now also higher.5 This is a multiplier effect on the interest expense we must pay to account for our excessive spending in the past.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) writes:

Net interest outlays are projected to account for a growing share of total federal outlays over time. In CBO’s projections, that share increases from 8 percent of outlays in 2023 to 13 percent in 2032.6

The chart below shows the total debt and the average interest rate for that debt over time.7 An increase in the total debt and an increase in the average interest rate is not a good combination.

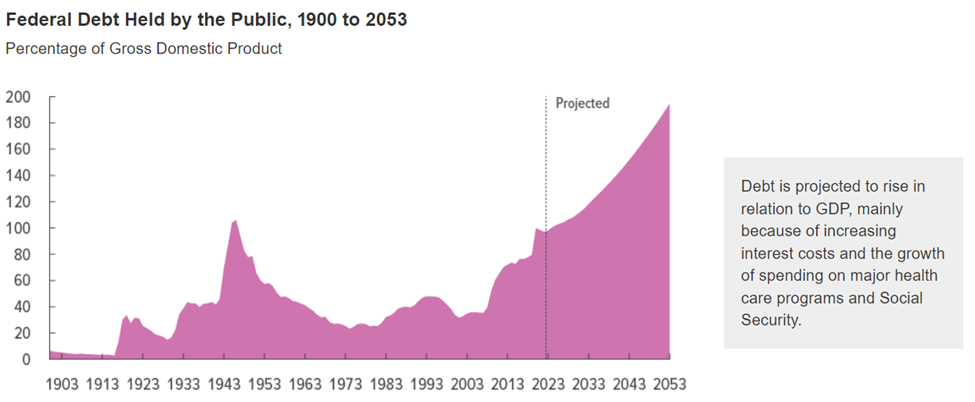

The Congressional Budget Office produces the historical debt held by the public and an ominous projection.8

Closing the Gap – Financial Analysis

Here’s an interesting tidbit from NOTE 26 of the Annual Treasury report.

…closing the fiscal gap requires running a substantially positive level of primary surplus, rather than simply eliminating the primary deficit. The primary reason is that the projections assume future interest rates will exceed the growth rate of GDP. Achieving primary balance (that is, running a primary surplus of zero) implies that the debt held by the public grows each year by the amount of interest spending, which under these assumptions would result in debt growing faster than GDP.9

Interpretation – we can’t just balance the budget; we must run a sustained surplus for some time, just to keep the debt from continuing to grow.

Interest Expense & The Fed

- Interest expense on our debt has been manageable in recent decades due to extraordinarily low interest rates, around 2.4%.

- If interest rates revert to the historical mean, the cost of servicing our national debt will become unaffordable, even if the underlying debt itself does not increase, which it will.10

- Rate increases by the Fed to combat inflation, (also caused by the Fed), translate into higher borrowing cost for the U.S. Treasury.

- Higher borrowing costs on an increasing debt load create an unsustainable debt service level. At some point, insufficient funds remain (after interest expense) to pay for promised benefits, programs, and entitlements.

- The Fed also has a theoretical limit on rate increases before it threatens the stability of the banking system. An unacceptable risk.

- Swift rate increases by the Fed put commercial banks in a quandary, many with a troubling “duration mismatch” between capital requests from depositors and capital tied up in fixed income investments. This would have been fine if held to maturity, but capital outflows from customer withdrawal requests forced banks to sell these securities early, at discounts to par value. Banks therefore must take a sudden hit to their balance sheets, straining their financial well-being.

- Fragility in the banking system constrains the Fed’s actions on further rate increases.

For both reasons (affordability of debt service and the future health of the banking system), the Fed almost certainly kept rates lower than it would have otherwise needed to fight inflation.

Conclusion – The Fed Won’t Continue to Raise Rates – Because It Can’t

Based on this, I would expect higher-than-desirable (2% target) inflation to linger longer than what is currently forecasted.11 12

Potential Debt Solutions

There are only a few known solutions to our excessive debt, discussed in the sub-sections below. In my estimation, none of them solve the problem individually. Consequently, we must enact a combination of these solutions simultaneously.

Reduce Government Spending

Reduced spending comes in two flavors:

- Broad-based reduction in spending.

- Reducing wasteful spending.

How much waste is there in the budget? A lot. We all know this instinctively. But how much exactly? It’s hard to say. But let’s suppose (hypothetically) that we could cut broadly by 10% (across the board) and also identify and cut another 5% through targeted waste reduction. Does this combined 15% spending cut balance the budget?

No.

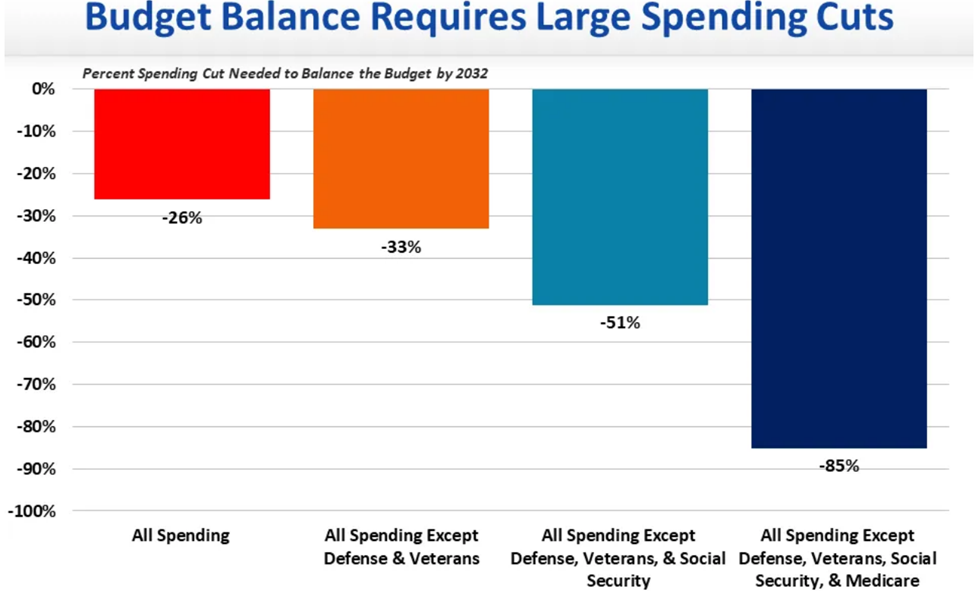

- The chart below (with the really unfortunate color scheme), produced by the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, shows we would need to cut 26% across the board, on every single line item in the budget, to simply balance our budget by 2032.13 To be clear, this is just to get us to break-even by 2032. This does not reduce our debt. It simply means we stop adding to it.

- The blue bar on the far right of this chart shows we would need to cut 85% of all remaining budget items if we do not touch spending on the largest four categories: Defense, Veterans, Social Security, and Medicare. Wow.

- There are practical limits on how much spending can be reduced each year before everything falls apart. Obviously, an 85% spending cut is not feasible. In fact, a 26% cut is a showstopper as well. There is no way politicians would ever cut that deep and agree on the exact items to cut. They wouldn’t even agree on an equal 26% on everything. No possible way.

Conclusion: Reducing spending alone will not balance the budget.

While we might make some single-digit percentage headway on spending cuts, there are other tools in the toolbox, including the one no politician will discuss publicly – increasing taxes.

Increase Taxes

The government collects money on the circulation/flow of money, mostly from individual citizens and residents, but also (to a lesser extent) on corporate profitability.

Currently, we would need to increase taxes by X% to balance the budget. What is X? Well, that depends on how the tax rate is implemented and how progressive it is. Here are some example scenarios of tax rates needed to balance the budget:14

- If raising rates on only couples making greater than $400,000 per year, the top tax rate would need to be 102%.

- If raising rates on only couples making greater than $250,000 per year, the top tax rate would need to be 90%.

- If raising rates on only couples making greater than $150,000 per year, the top tax rate would need to be 80%.

[Note: these figures ignore the behavioral changes these groups collectively make if taxed this high – a key point to consider.]

Obviously, these rates are quite high, which brings up a discussion about theoretical limits of taxation.

Theoretical limits on taxes bookend the available options on the “increase taxes” strategy.

- The bookend on the low end of the tax scale is 0%. That is, collect no taxes. This results in $0 for the government budget, obviously.

- The bookend on the high end is 100% tax. This means the government takes every dollar every citizen makes (and spends). This also results in approximately $0 in taxes collected, because everyone quits working and spending (or quits reporting it).

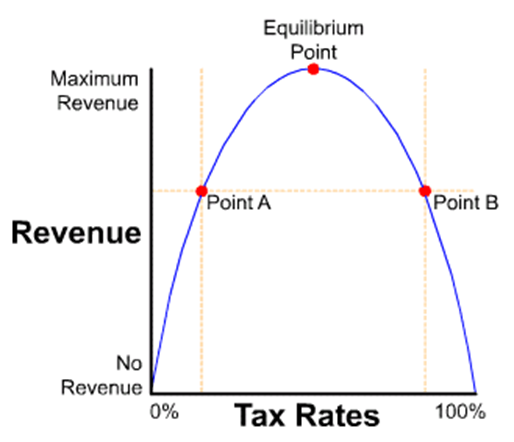

What happens between these two bookends is officially referred to as the Laffer curve. The simplest version looks like this.

Everyone is entitled to their view on where we are collectively and individually on the Laffer curve. Some people might think we are near Point A on the curve (see above) and therefore argue we should increase the tax rate to increase tax revenue collected for the government budget. Others might argue we are at Point B and would therefore argue we should lower tax rates to increase tax revenue.

The truth is, no one really knows where we are on this curve because it’s a complex problem. And, both positions can be simultaneously correct. For example, some citizens may be at point A, while others are at point B. In this case, we are collectively at neither point A nor point B, only individually.

The issue is that people tend to have the same position on taxation as Bob & Sally, a swell (hypothetical) couple who make $95,000 per year. Bob & Sally think everyone making more than $100,000 is due for a tax increase and they (and those making less than $100,000) are due for a tax break.

The dilemma – everyone is Bob & Sally. Some Bob & Sally’s make $45,000/year. Other Bob & Sally’s make $150,000 or $650,000 per year, or more. Regardless of income, almost everyone holds the Bob & Sally position. Tax people making more than me, but not me.

Layer on top of this another notion we should also consider – should the government optimize for maximum tax collection in the first place?

The answer to this question is also complex, and likely reveals how one thinks about the efficiencies of governmental capital allocation compared to say free market capital allocation.15

Regardless of where we actually reside on the Laffer curve, there’s not an optimal tax rate between points A and B that collects sufficient revenue to balance the budget. Even if we land on the peak of the Laffer curve, I just don’t think the crest is high enough.

Conclusion: Tax increases alone will not solve the budget problem.

Further, substantial increases in tax rates introduce the real risk of landing us (collectively) on the far-right side of the Laffer curve, damaging the economy and lowering tax revenues, a double whammy.

Promote Inflation

- The hidden benefit (agenda from a U.S. government budget perspective) of inflation is that we borrow dollars at today’s value and pay back those loans with dollars of lesser value.

- Inflation isn’t good if you save money and invest it conservatively (or retain cash), but it helps the government’s debt problem (and individual mortgages).

- Inflation is painful for the economic health of the citizens, especially the most financially vulnerable – those on fixed income (the elderly and retired) and low-income earners (because inflation increases the costs of goods before compensation increases catch up).

- The main issue – the debt is so large (relative to GDP), we need considerable inflation to chip away at it.

- Here’s a key political point, inflation does not require politicians to talk about raising taxes, cutting spending, shrinking promised entitlements, and/or enacting insufferable measures of austerity, but inflation enacts all of these.

Conclusion: Inflation alone will not solve the budget problem… nor should it (ideally) be part of the plan.

Divest Government-Owned Assets

The U.S. Government owns a lot of tangible and intangible assets. These could be sold to raise funds for debt reduction. This is akin to selling part of your house to pay your mortgage. Not the best idea, but nevertheless, an option.

Default

Defaulting on our debt equates to a global economic calamity. This is the solution that naturally evolves if the other solutions above fail, or if we fail to enact them, or fail to sufficiently act on them.

Do Nothing

This is the “bury our heads in the sand” approach and precisely what we have done thus far.

Under this scenario, our only hope is that some technological innovation (like artificial intelligence or near-free energy from cold fusion, or some similar massive technological benefit) leaps us forward in productivity and economic growth such that we grow out of the debt problem. This is entirely possible. Not probable, but possible.

The obvious concern with this path is that we simply continue to increase our spending with productivity gains. If past behavior is a predictor of future choices, this is exactly what will happen.

Summary of Debt Control Options

The last two options (Default & Do Nothing) aren’t really viable options (and they may be the same option). I only mention them because they are possible paths, and I am outlining all available options.

The first two (cut spending/waste & increase taxes) address the continual government deficit, which in turn affects the accumulated debt. But each alone is insufficient.

The third solution (inflation) is essentially a hidden tax hike, but more subtle and less transparent. In other words, inflation is the backdoor, craven implementation of increasing taxes and reducing the value of benefits without announcing it. Also, inflation is broad-based and therefore does not trim wasteful spending from the budget.

What Needs To Be Done – Waste Reduction, Taxation & Austerity

Here’s a quote from the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) report quantifying what would be required to bring the U.S. debt back down to 100% debt-to-GDP.

…if policymakers choose to achieve a debt-to-GDP target of 100 percent—the level the federal government reached at the end of fiscal years 2020 and 2021—they would need to make policy changes over a 75-year period (fiscal years 2022 to 2096) that increase projected revenues by 32 percent, reduce projected noninterest spending by 25 percent, or a combination of the two. The projections show that the longer such policy changes are delayed, the more significant the changes will need to be.16

Given the size of the increase in taxes required (32%) and the required cuts to entitlements (25%), we cannot do EITHER/OR. It must be a combination of both, plus other ideas. As much as I would like to say we could simply reduce spending and not increase taxes (because no one wants that), we simply must do both. And we must do it quickly.

If we were to implement immediate changes, and work both sides of the equation half each, we would need to increase taxes by 16% and cut spending by 12.5%. Some comments:

- A 16% tax increase does not mean your tax bracket moves from 20% to 36%. It means you might move from 20% to 23.2% (a 16% increase in the tax rate). When we say it that way, it seems within the realm of reason. I mean, it’s not fun. Certainly, we’d rather have the money than pay the tax. But if the American people knew with certainty that the additional increase would go directly to, and only to, debt reduction, we might just be willing.

- By contrast, cutting government spending, immediately, by 12.5% seems like a lot. That one is more difficult, partly because it’s a lot of money not being spent, which certainly means laying off government jobs, which results in fewer people working, less spending, lower economic activity, potential corporate layoffs, lower taxable incomes, etc. It’s all interconnected and circular and might prompt a recession. In fact, almost certainly.

Caveat: There’s a case to be made that we could selectively trim fraud and waste, which would help. Perhaps through targeted cuts of wasteful spending, we could reduce 3-5% of the budget, if only lawmakers could agree on what is considered “wasteful”. Certainly, nothing in their home state.

Before we get too excited, let’s keep in mind, this whole discussion from the GAO is for a target debt/GDP ratio of 100%. That puts us roughly in line with those countries continually teetering on bankruptcy.

Taxing Individuals and Corporations

While we are on the topic of taxation, I’d like to note that most tax revenue is from individual payers like you and me. We (individuals) pay about 47% of the taxes collected. Corporations pay about 9%.17 The point here is, there seems to be this idea that we can simply raise corporate taxes and make up the difference. Two points on this topic:

First – even if we increase the corporate tax rates by 50% (unreasonable), corporations would only pay ~4% more of the tax revenue the government collects. There’s just not enough there to close the debt gap.

Second – as we tax companies more, there’s less cash left to reinvest in corporate growth (job creation). If we overtax companies, we grind the economy to a halt (same story if we overtax individuals).

Conclusion

The United States is on the precipice of an economic calamity, owing to the size of our national debt and the increasing deficits we continue to heap upon it. It would be difficult to overstate the seriousness of the national debt issue.

At some point, there will be a great reckoning. Either we sludge through a potentially prolonged recession with tax hikes AND budgetary austerity measures, or we risk the solvency of the entire nation. Or, best case scenario, some technology comes along and saves the day with a massive economic bursts of efficiency and productivity. Could happen.18

Our political leaders must act quickly and decisively. They must make unpopular decisions and be headstrong in their tactical implementation. Aligned with this, we as citizens must vote to elect leaders who are willing to tackle what I believe is the single largest predator upon the future viability of our nation. We must have a season of significant austerity, waste reduction, and tax increases.

Nobody likes to hear that, including me, especially the part about tax increases, but the math is clear. The debt has garnered such momentum that just one or two of the components above will not suffice. All three are required to stop the national debt from consuming the entire economy.19

Without significant changes ahead, none of which are fun, I believe we are on the edge of an economic collapse.

The Dilemma

Here’s the dilemma – no politician will implement an austerity / waste reduction / tax increase policy. Why not? Because anyone running with the platform of lowering entitlements and increasing taxes is doomed to never get elected. They don’t even survive the primaries.

Who gets elected instead? The politician who promises free money and lots of benefits.

Give me money + give me free stuff = get my vote

The lack of basic economic acumen amongst our citizenry is perhaps the doom of a freely democratic society.

And maybe that’s how it ends.

It would seem that, built into the very foundation of a republic, for which we stand, is its own downfall. Human nature’s inherent fear and greed, the driving forces of capitalism, apparently holds no room in the inn for austerity and common sense.

Bonus – Some Politics

I personally would vote for almost any reasonable candidate that would run on the debt reduction platform initiative of:

- Reduce wasteful government spending.

- Lower entitlements

- Higher taxes

I would encourage you to consider the same. Otherwise, it won’t really matter if you are on the left, or the right, or in the middle, or somewhere else completely, because The Republic will be bankrupt.

What might take its place? It won’t be a void. It will be something. It will definitely be something. And that next something won’t wait for everything to collapse before it arrives. It will arrive quite suddenly, an upheaval, as a wave of realization sweeps across the nation that we waited too long and essentially have no real viable options to pull ourselves out of the debt we have incurred.

Maybe I’m just Chicken Little running around yelling, “The sky is falling! The sky is falling!”

But I don’t think so. The math is quite simple, and the problem is that serious.

Related Post:

Where to Cut Federal Spending – An Economic Plan for the U.S. – Part 1

Where to Cut Federal Spending – An Economic Plan for the U.S. – Part 2

Where to Cut Federal Spending – An Economic Plan for the U.S. – Part 3

My Key Takeaways from Reading the Federal Budget

The Real Reason the Fed Will Resume Printing Money

Follow Past Midway if you would like an email notification of new posts.

FOOTNOTES:

- And bought significant put options on SPY in Q4-2019. But that’s a story for a future blog post.

- That is, the Fed is politically influenced. “But The Fed is independent,” you counter. Sure.

- Source.

- Of the 87 countries where the IMF tracks this data. Source. Also, the U.S. benefits from the sheer size of its economy and from the dollar being the global reserve currency. These attributes have allowed the U.S. to maintain a greater debt leverage compared to other nations, but we might have exceeded the grace of these caveats.

- To be clear, the interest rate does not go up on the entire debt amount, just the newly issued debt. As previously issued 1, 10, and 30-year Treasury bills, notes and bonds mature, new debt is issued to pay off these prior notes, with the new debt at current rates, which are mostly higher.

- Source: CBO. Options for Reducing the Deficit. Page 2.

- Source: U.S. Treasury

- Source: Congressional Budget Office

- Source: FY21 – U.S. Treasury Report (pages 160-161) (NOTE – I’ve been writing this over several years, before the most recent report was published. I didn’t feel like updating my quotes.)

- To give you a sense of scale: The average interest rate on marketable U.S. debt in 2023 was ~2.7%. 2022 it was ~1.5%. 2009 – 2021, the average rate was ~2.0%. This was the Fed target, following the 2009 Financial Crisis. 2001 – 2008, it averaged 5.0 – 6.5%. 1990’s ~6.9%. 1982 – it peaked at 10.8%. Yikes! Across the most recent 40 years, the average is around 6%. If the interest rate on debt simply moved to the recent historical average of ~6.0%, our interest expense would begin to snowball. And, as that interest expense climbs with the issuance of new debt, the concern will increase that the U.S. won’t be able to pay the interest. This concern will drive rates even higher. This is a troubling feedback loop. Source 1. Source 2.

- Many experts assume 2024 will bring inflation back down to the 2% target, so I recognize that I might be an outlier on this point, but I’m sticking to my thesis because inflation has a way of lingering and filtering its way through the economy slowly.

- Also, there has been a substantial government subsidy that has largely gone unnoticed. In an effort to tame inflation, the Biden Administration released the Strategic Oil Reserves, depleting it by a little more than half. Source. This is effectively a government subsidy on oil and gas prices (and all products and derivatives made from oil). At some point, and we are likely at that point, we will need to replenish the reserves, which will reduce supply from the market and increase prices, causing lingering inflationary pressures on the broad economy. The fact that we dipped into the Strategic Reserves for economic reasons should be an entire blog post itself.

- Source.

- Source.

- If you’re interested in more on this concept, consider listening to speeches by the famous American economist Milton Friedman (1912 – 2006).

- Source: Statement of the Comptroller General of the United States, U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO)

- Source: U.S. Treasury

- Artificial Intelligence has the capacity to usher in massive advances in productivity and growth and might add significant counter-acting deflationary pressure to the macro economy.

- For the record, I understand the supply-side economic theory of lowering taxes to spur economic growth to yield greater tax revenues. However, as far as I can tell, the evidence does not support that we are on that side of the Laffer curve. If we were, this might work… but we are not.

I think my two comments, because I believe you are right, is 1) God help us all & 2) perhaps this is the one good thing about being old.

I wonder if you’re placing enough value on the “divest of assets” solution? The Republic might look different, but we’d survive. What wealthy nation can we sell Puerto Rico to? Would Canada buy (if they could afford it) my home state of Michigan? Maine? Perhaps India will be the economic powerhouse of the next 100 years and they’ll be willing to buy California? Or maybe just Hawaii? Ok, Ok so we’re not willing to take stars off the flag…..the U.S. owns a LOT of real estate. We might have to sell Yosemite National Park to the lumber industry. Do we own the Moon?

Andy, I really appreciate the time and effort you put into this!