When someone says, “I love you,” what exactly do they mean?

To what extent do they mean it? For what duration do they mean it? And do their subsequent actions continue to support the original claim consistently across time?

These questions came to me while re-reading a few pages from Gordon Livingston’s wonderful book, Too Soon Old Too Late Smart.1

Probably the single most confusing thing that people tell each other is ‘I love you.’ We long to hear this powerful and reassuring message. Taken alone, however, unsupported by consistently loving behavior, this is frequently a lie – or, more charitably, a promise unlikely to be fulfilled.

This last phrase – a promise unlikely to be fulfilled – contains the idea I’d like to explore further.

The Duration of Expressed Love

While English excels in many areas, including efficiency of communication, it lacks the nuanced vocabulary to express and portray love compared to other languages. Consequently, we love our ice cream and our children equally in English. This can be limiting and problematic.

The range and variation of verb tenses in a language also influence how affection is expressed. Here too, English tenses fail to capture the complexity of love.

Love, in the verb form, expressed as “I love you”, is present tense. Grammatically, in English, this implies right now, in this instant.

I love you in this exact moment.

Fine.

But when someone speaks “I love you” into existence, we generally interpret this as a declaration that the emotion and commitment of love from another exists right now and continues to exist in the next moment, and hopefully perpetuates into subsequent moments thereafter, indefinitely. The duration of expressed love from this present tense statement feels open-ended to the recipient. At least, that is how we interpret it when we hear it – or at least what we hope it means (credit my wife Sofie for this last phrase).

For long-term relationships, we might assume this expression of love also implies the present perfect tense:

I have been loving you.

The perfect tense:

I have loved you.

And perhaps past tense forms as well:

I loved you.

I was loving you.

But maybe less so the modal forms:

I should love you.

I should have loved you.

I should have been loving you.

Or the perplexing pluperfect conditional form:

I should have had to have been loving you.

(although complex, this is strangely comprehensible.)

Pluperfect conditional love conveys a sense of regret over a broken relationship with the subsequent realization that love sometimes necessitates a force of will – to consciously and actively choose to love, especially when unfelt. This is a key ingredient missing from many relationships – the notion that “I should have been forcing myself to love you.”

Life experience teaches us that the raw emotion of love may have a half-life. It morphs across time and sometimes fades. In this sense, there might be an expiration date on the validity of “I love you” as a statement of fact. This is precisely because too many of us fail to embrace the pluperfect conditional meaning of love – to will into existence a continuous and perpetual love for someone despite feelings to the contrary.

If love grows through the on-going drama of shared experience,2

Love’s depth is forged in the quiet resolve to choose it, through the forced will of acting out love regardless of how we feel, even if the heart wavers.

Love is easy when it is felt. Less so when it isn’t. But felt love is a veneered, immature version of the deeper love we all crave.

We each need to feel loved most when we are the most unlovely and unlovable, when we do not reciprocate love.

So, what is the half-life of love? How far into the future do we expect to assign a positive probability to the “I love you” statement?

Livingston implies the phrase “I love you” is a promise.

A promise implies future deliverables.

A promise does not expire.

If we promise to keep a secret, generally people understand this to mean into perpetuity, or at least an indefinite period until it no longer matters. If someone tells us a secret and we promise not to tell others, but then blab it a week later or a month later, our counterpart will feel we have broken our promise. They don’t think, Well, it’s been a few weeks, so I guess it’s OK.

One might suppose the phrase “I love you,” as a promise, a most precious promise, would hold the same indefinite duration as a regular promise, if only we meant it this way. Maybe this is the better framing of how we should think about love. When we say I love you to someone, in our minds, we should simultaneously think, I promise to continue to love you indefinitely, even when you are unlovely and when I don’t feel it… and I promise to honor that promise.

This sentiment brings a whole new level of commitment and authenticity to the expression of love. This is what transforms love into Love.

Love Demonstrated by Our Actions Over Time

My wife (Sofie) and I seem naturally wired as minimalists. Consequently, two years ago, we were decluttering the attic and purging excess belongings when I came across a box of old letters. I had saved every letter my friends wrote to me from 6th grade until letters became emails. It was nostalgic to read through them, which I took time to do that afternoon, something I had never done before. Anyway, I just couldn’t throw away some of these gems without first snapping a picture to archive them digitally.

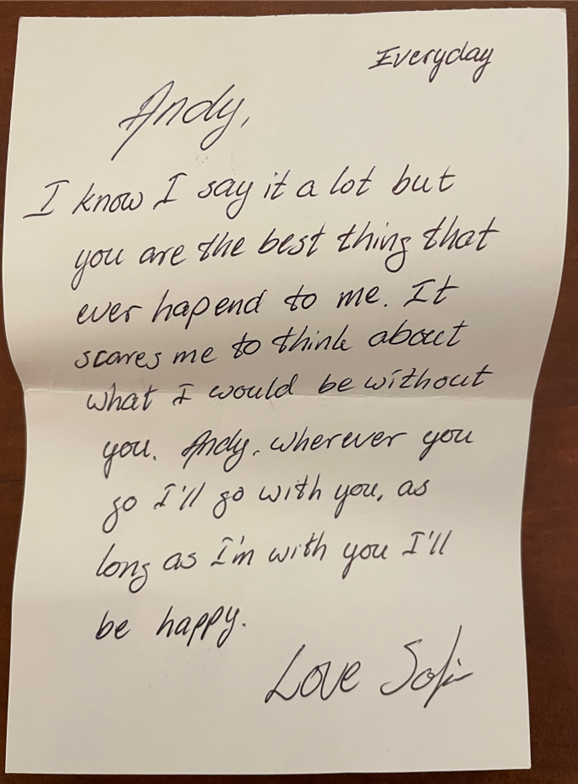

The note below from Sofie is one of them, likely written 20 to 25 years ago.

The date on the card is “Everyday”. This is what it means to make a promise of love without expiration.

Notice the note does not discuss “love” (except in the closing signature), but it exudes love conceptually all the same.

This is a very personal example of the pluperfect conditional form of love that illustrates the weight of our words and the continuous commitment required of them.

Sustained love is reaffirmed through our actions across time.

After 30+ years of marriage and testing the validity of this original note, Sofie could now say to me with perfect, unconditional truth,

I should have had to have been loving you… and I have.

A promise fulfilled.

Our Responsibility to the Amortization of Love

When we say “I love you” to another, do we assign an element of expected future time, effort, and care to that phrase and mentally commit our emotional and physical resources to the future deliverability of the promise we have just made? Or do we simply mean, “I love you right now in this very moment, but things might change, depending on how I feel, or how you behave”?

Which scenario would you prefer as the recipient of “I love you”?

To be accountable to the promissory nature of the phrase, do we amortize the proper energy reserves to fulfill the promise of future love in which we have committed ourselves?3

And what do we expect is the realistic decay function on our promised responsibility to love another when we utter this powerful phrase? Is it indefinite?

At a minimum, we should take the phrase more seriously, even revere it, if we are willing to love in the way we ourselves want to be loved.

A promise unlikely to be fulfilled – unless, and until, we continuously choose to fulfill it.

Related posts:

A Framework to Help Develop Your Criteria for a Spouse

Follow Past Midway if you would like an email notification when I post something new.

FOOTNOTES:

- Livingston, Gordon. Too Soon Old Too Late Smart. London. 2006.

- Credit this phrase to Tim Minchin.

- As I was reading an early draft of this blog post to Sofie, she said, “That is what we are doing when we get married. When we are at the altar, we are promising our commitment of future love to the other. But we don’t do that formally to others. Marriage is the only formal proclamation. But then you have the love to your children. It’s not a formal declaration. It just is.”

“Wait, slow down, I can’t type that fast,” I said, as I was feverishly trying to capture her words for this footnote… because it was good stuff on the fly.

“You don’t need to write any of that crap down,” she demurs, as normal, and walks away to resume showing her love to the rest of us through her unrelenting service to others.

Lovely (wink)

But it really is/was.

The best yet. The very best. I suspect many mothers would be totally surprised at such a writing from a son. I am not.

The one word I do not recall seeing is the word “cherish”. It’s the word I think of the most when pondering (often) the love I had from your dad. That example set by him is why this writing did not surprise me. As always, good job.