Suppose the Johnson family makes $100,000 per year (after taxes).

Yet, to maintain their lifestyle, the family spends $114,000 per year on food, clothing, utility bills, gas, school supplies, the dentist, entertainment, lawn mowing services, pool maintenance, etc.

Oops. They don’t have $114,000. They only have $100,000.

No problem. To bridge the gap between income and expenses, the Johnsons just plan to borrow $14,000 from the bank, just like they have done in years past.

But wait, there’s an additional complication. The loans from prior years have been piling up. Consequently, the family owes the bank a total of $898,000!1 Fortunately, the interest rates are low. Nevertheless, this cumulative loan amount requires an interest payment of $29,000 this year. The bank insists.

So, the family borrows an additional $29,000 to cover the interest payments on existing debt. It’ll be more next year, but that’s a problem for later.

Total borrowing this year now equals $43,000, $14k to cover the excess spending plus $29k to cover the interest payments.

In addition, the Johnsons have $145,000 in credit card debt. No payment is due this year, but eventually this loan must be repaid.2

Oh yeah, we almost forgot. One of the family members has multiple secret credit cards that the rest of the family does not know about. Shockingly, this one family member, and we won’t say who, has racked up $3.1 million in secret credit card debt. Yikes! But we’re not supposed to talk about that. That’s the nature of a secret.3

The Johnsons – Financial Summary Income $100,000 Expenses $143,000 Bank Loan $898,000 Credit Card Debt $145,000 Secret Credit Card Debt $3,100,000

There are at least three problems here:

- The Johnsons spend every dime they make (technically, they even spend dimes they don’t make). There’s no rainy-day fund. There are no savings. The family literally has nothing to show for all their spending. Rather than recognize they should reduce their expenses, they continue to have a great time and borrow to appear to keep up with the Joneses.

- With a $100,000 income and a $143,000 lifestyle, AND a total debt to date of $4.1 million (and climbing), the family has zero chance of climbing out of this debt spiral without a serious intervention. And even then, it’s dubious. Ask yourself, would you loan money to the Johnsons?

- Not only is the rest of the family in the dark about the $3.1 million in secret credit card debt, so is the bank! Because the family has always paid the interest historically, the bank got lazy and didn’t pull a credit check on the family. Eventually, one of the bank’s investors will audit the Johnson’s financials and discover they cannot possibly repay the bank… and there are other families using this same bank in similar positions as well. Suddenly, the bank’s investors realize the Johnsons, the Smiths, the Browns, and many others are insolvent, as is the bank itself now, and potentially some of the investors too. The investors will conclude that they probably shouldn’t tell anyone. Otherwise, everyone with deposits at the bank will want to withdraw at the same time and put their money elsewhere, somewhere safer. A classic run on the bank. Bank failures don’t happen fast. They happen slowly. The “sudden” part at the end, the failure, only happens when people REALIZE the bank is in trouble. Banks fail long before people realize it.4

I think you can see the severity of the problem here. It’s bigger than just the Johnsons and their loads of debt and overspending, although that’s pretty dire itself.

At this point, I’m sure you have gathered this is an analogy to the financial health of the U.S. Federal government (especially if you read the footnotes). These are the exact financial ratios for the U.S., applied to a family’s personal household budget making $100,000 per year, using my U.S. economic projections to 2033 (discussed below).

What We Know…

We know the national debt is a problem.

We know our annual spending surpasses tax revenues, resulting in a deficit that further contributes to the national debt.

We know the potential solutions available to help bridge the gap between revenue and expenditures.

We know that addressing our significant wasteful spending (one of the potential solutions) is crucial to achieving a balanced budget.

We know the opportunity to address this is fleeting, as we stand on the brink of an economic black hole from which there is no escape.

The Challenge

Many people, myself included, have argued that we need to rein in government spending.

Fine. That’s easy to say generically, without having to be specific.

However, no one in leadership appears willing to specify PRECISELY where these cuts should be made – perhaps because they have not thoroughly analyzed the budget or lack the political courage to articulate the exact line items to cut.

The problem is that any spending reduction significant enough to make a difference inevitably faces strong opposition from a sizable group of voters, lobbyists, friends, family, and neighbors who benefit directly from it. Their stance often boils down to: “Cutting other programs is fine, but not this one – this one is a good government program.”

So, at the risk of stirring up controversy and maybe pissing off nearly everyone, I thought I’d take a stab at a specific spending reduction proposal. Sometimes, someone just needs to be the first to voice a viewpoint on a complex, controversial topic to get the conversation started.

Outline

This blog post is a beast, at least for me, primarily due to the research and analytics required. I have therefore divided it into three parts… partly to buy myself some time.

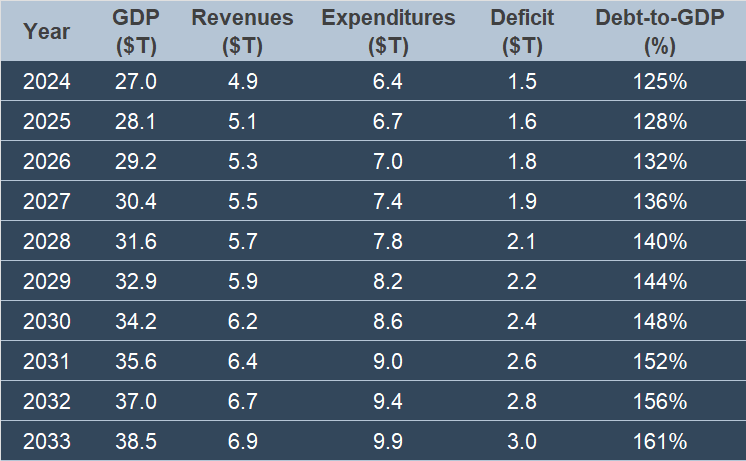

Part One – that’s this post. I created a simple, 10-year projection of the U.S. government finances, to illustrate where we are economically and where we are headed as a nation. This is what I used to create the family budget analogy above.

Part Two – outlines the available options to help regain our financial footing.

Part Three – If we must reduce government spending as a mechanism to help balance the budget, (and we must), where exactly do we make the cuts? In this section, I plan to offer specific recommendations… assuming data is available in sufficient detail to capture granular ideas.

Let’s get started…

Part 1 – The Financial Future of the U.S.

Should we really be concerned about the economic health of the United States?

Navigating conflicting opinions surrounding complex topics like government programs, spending, accounting, and budgets can be challenging. Consequently, whenever possible, I prefer to start from raw, reliable source data (just the facts) and construct a view from well-reasoned first principles. This bottoms-up approach is the guiding aim of this article.

So, let’s look at the data.

Using the proposed Budget of the U.S. Government (2025) and the “Spending Projections, by Budget Account” spreadsheet produced by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) (this link will download the Excel file) as the sole source documents, I developed a 10-year projection of the nation’s financial health, based on straightforward, realistic assumptions about GDP growth. I also assumed no changes to the tax code.

My goal is to keep the analysis simple. We do not need overly complex financial models to illustrate the gravity of the situation, because the numbers are so undeniably dire, just like the Johnson family we met in the opening segment.

A Simple Economic Projection

To project the financial health of the U.S. federal government through 2033,5 we only need to consider the top-level components: changes in GDP, Revenues (taxes collected), Expenditures, Debt and the related Interest on debt.

Assumptions

REVENUES

- Federal revenues are primarily composed of income taxes, payroll taxes, corporate taxes, and other receipts. With no changes to the tax code, revenues typically grow in line with nominal GDP.

- Historically, tax revenues are ~18% of GDP.

- Assuming GDP grows at an average annual nominal rate of 4% (2% real growth + 2% inflation), revenues should grow proportionally.

EXPENDITURES

- Key expenditure categories include mandatory spending (Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid), discretionary spending (defense and non-defense), and interest on the debt.

- Mandatory Spending: Grows a bit faster than GDP due to aging demographics and healthcare inflation.

- Discretionary Spending: Historically declines as a percentage of GDP, unless expanded.

DEBT & INTEREST

- Annual deficits are the difference between expenditures and revenues. Deficits add to the total debt.

- As the debt increases (or interest rates, or both), interest costs rise.

- We will assume average borrowing costs rise moderately.

Given these assumptions, here’s how we progress through 2033.

Conclusions

- The projected growth in debt relative to GDP suggests an unavoidable strain on fiscal sustainability. If left unaddressed, interest payments on debt (currently consuming ~24% of government revenues) will eventually exceed tax revenues collected. It is therefore an unsustainable budget and an unstable financial future.

- Consequently, we need significant fiscal reforms to reduce debt to more manageable levels.

The meta themes are,

Unsustainable finances lead to the unstable economic health of a nation, a welcome mat for the future twin guests of chaos and anarchy.

The goal is to address the national debt before widespread negative sentiment erodes confidence in the U.S.’s ability to meet its interest obligations.

The key point isn’t whether or not we can make the payments, it’s the confidence of investors and fellow countries that we will continue to make them in the future. As soon as confidence is lost, there are suddenly very few buyers of U.S. debt… and the whole program falls apart, seemingly instantly, even while we can still make the payments.6

This concludes Part One… teeing up the severity of the problem.

Part Two – Viable Options to Shore Up the U.S. Balance Sheet.

Part Three – Specific cuts I am proposing to the Budget

PART 1 – APPENDIX

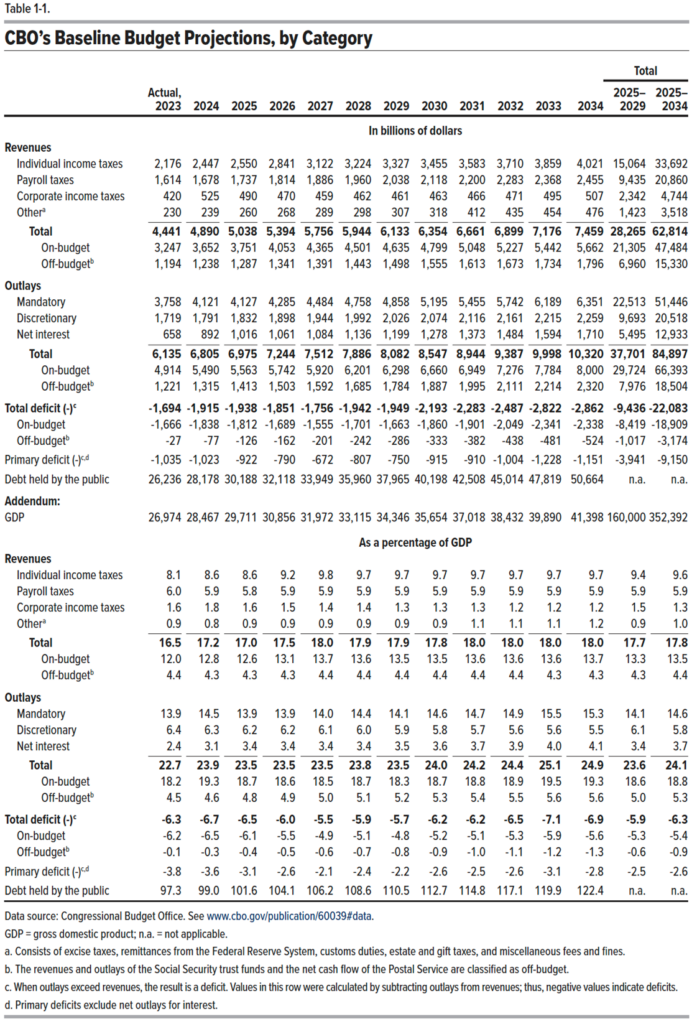

I would later find the Congressional Budget Office’s official 10-year financial projections (the link will download the Excel file, also pasted below), which are comically close to my projections. The main difference is, the CBO assumed slightly higher GDP growth and an increase in taxes collected (because they forecasted higher tax rates). Bottom line – it’s quite close.

I would also like to point out, as a test for projection accuracy, we can look at the CBO’s 10-year projections they made 10 years ago (in 2014) for the year 2024 and compare projections to reality. In 2014, the CBO showed a projected deficit in 2024 of $960 billion. This year, the 2024 full-year deficit is projected to be $1.7 trillion. So, that’s pretty far off.

Also, I began my projections with an estimated $1.5 trillion deficit in 2024 rather than the CBO’s projected $1.7 trillion. So, my projections might even represent a more optimistic scenario than reality.

Follow Past Midway if you would like an email notification when I post something new.

FOOTNOTES:

- This is not a mortgage. A mortgage is backed by an asset – the house. This debt, by contrast, is just money spent on stuff and services the family has consumed. There are no assets to sell to get this money back. It’s just gone… but they still owe the bank.

- This is analogous to the Fed’s balance sheet, which stands at $7 trillion in 2024 and projected at $10 trillion in 2033, assuming the same ratio to GDP holds.

- This is an estimate for the off-balance sheet debt the U.S. government also owes, due to unfunded liabilities. But apparently, we don’t count that debt as debt because we do not track it and report it. Don’t tell.

- This isn’t a perfect analogy, but it’s close. To ensure everyone is following, the Johnson family is analogous to the U.S. government, which includes the entire institution of government as well as individual citizens like you and me. The family members are essentially governmental departments. The known credit card debt is the Fed’s balance sheet, hence no interest payments. The secret credit card debt represents the U.S. government’s off-balance sheet debt (unfunded liabilities). The bank is the U.S. Treasury, and by extension, all the buyers of U.S. debt (Treasuries), which include individuals, institutions, and other countries. Other families are other countries, also issuing debt. The bank’s investors are essentially politicians who are incentivized to turn a blind eye to the problem of the “bank’s” financial health. I know, it’s confusing. The main idea was to depict the health of the U.S. financial issues within the context of a family budget, using exactly proportional numbers to the $100,000 family income.

- Coincidentally, 2033 is the year the CBO projects the Social Security Trust Fund goes to $0 (of course, this is the first year I would be eligible to receive it). That’s OK, my guess is it will reach $0 a few years before that.

- It will be much like watching a train wreck from an airplane 10,000 feet up. You can see what’s going to happen long before the collision, but the passengers on the train only feel the sudden impact.

Very well done. Nice way to show how bad it is by using a family budget. I am looking forward to Part 2.

Obviously, you’ve touched on this topic before, so thanks to you, my kiddos and husband, I’m well-versed in the basics. But I appreciate the way you always lay it out in an easy to understand format for those of us who don’t want to do things like read the entire federal budget. Lol.

I have a few questions, but I think one of them at least, will probably be covered in part two.

1. Covered in part 2? – raising taxes or other options to increase income vs or in addition to spending cuts.

2. If your current projections are very close to the CBO current projections, but the CBO was so horribly far off in their 2014 to 2024 projections. What factors did they miss in their last 10 year projection, that you both may also have missed this time? Not sure I worded that clearly.

3. My third question might be a part 4(?) – Are there any factors that you believe could disrupt the current situation (outside of decreasing spending and in increasing revenue), like war? War has traditionally been a global financial disruptor. Wondering if there are any other financial disruptors, and if you believe it would be good or bad financially (obviously war is just bad, but talking dollars here) for the US, and if it matters who that war is between.

Great read as always

Christy – great questions.

1) Yes, I will cover available options to (better) balance the budget in Part 2… stay tuned.

2) I literally had the same question to myself when writing this… but didn’t feel like going into that much nuance. I suppose the main factors for the missed projections were: (a) all the money printing by the Fed that caused inflation and (b) all the debt incurred by the Federal government to give away so much money during the same time period. Both were excessive. And therein lies the single biggest issue with making future projections… that we assume the future will behave “normally”.

3) This question is perhaps too open-ended to provide a well-thought out answer, but in general, I would think of the things that might happen in several broad categories:

– Unforeseen Events: natural disasters, pandemics, war, trade conflicts, rogue asteroid, alien invasion 🙂

– Sentiment: perhaps the world sentiment toward the U.S.’s economic health shifts suddenly and people began to question if the U.S. is in fact the right destination for “flight-to-safety”. This would cause a global economic disruption.

– Reserve currency: a shift to another currency as the world’s reserve currency.

– Weather: particularly that affects food production (or lack thereof). This would produce extreme economic volatility and general instability.

– Technological Advancements: Pros and cons (although the “Pros” tend to win in the long-term economically for this category).

– Unaddressed Debt Crisis: I advocate this is our single biggest economic risk to address because it is known with certainty. Hence, this three-part blog post.

– Stuff no one has ever thought of: “risk is what is left after we have thought of all the risks”.

A 2nd reply to your comment related to accuracy of projections… because I just found this.

In 2024, the White House “Office of Management and Budget” projected the 2025 Budget would produce a deficit of $1.781 trillion, or 6.1% of GDP.

Just six months later, the same organization produced the Mid-Session Review for fiscal year 2025.

The Mid-Session Review shows the 2025 deficit projected to be $1.878 trillion, or 6.3% of GDP.

This is a 5.4% error rate from projections (for the worse) after just six months.

This illustrates how difficult it is to make accurate projections for complex financial systems.

Just saw these replies. while reading part two I went back to look if you had answered. Need some sort of notification system that you answered my questions. lol.

Thanks so much for the thoughtful replies. Looking forward to part three as that seems like an extremely arduous task.

Also, your answers to my third question we’re both thoughtful and hysterical

Interested to see parts 2 & 3.

Have some similar questions as the ones my mom asked in her comment, but nevertheless a good read and start to what i’m sure will be a great blog post trilogy.