I have mentored high school students, college students and young adults for several decades, in several capacities. In doing so, I have observed recurring motifs related to the internal struggles faced by modern youth.

Young people contend with a smorgasbord of issues. While each young person is unique, careful observation across several decades has revealed meta themes sustained across time.1 These issues, discussed below, may come as no surprise to you, but it feels important to articulate my observations.

Mentoring & Pattern Recognition

Mentoring students who are not your own children allows for more objective observation and sometimes more candid conversations.2

The largely unspoken challenges that shape the lives of students today only occasionally bubble to the surface in conversation. These challenges are nuanced and subtle, a weak signal buried in the noise of life.

Parents are well-aware of bullying, anxiety, depression and, to a certain extent, substance abuse, particularly the variety found in the medicine cabinet at home. But other issues lurk deeper and are less frequently mentioned, unless you work with teens, for years, and ask probing questions… and listen… and think about the recurrent elements.

I should also note that most of my career has capitalized on an ability to identify and extrapolate patterns and signals from noise – to structure unstructured data. It’s safe to say,

Much of what young people discuss is unstructured, wonderfully unstructured, as is much of life.

Powerful Conversations

For several years, I facilitated a particular conversation between 11th – 12th high school students, intentionally designed to spotlight motifs otherwise muted within the broader symphony of growing up.

Initial questions were light, designed to warm the room to conversation and perhaps even invoke a few laughs.

Did you ever pee your pants in elementary school?

Laughter is good medicine and opens hearts and minds for more serious discussions to follow. The early questions led to the more pressing questions, which sounded more like:

“What do you think [guys/girls] struggle with most?”3

and the related question,

“What would you like the [guys/girls] to better understand about [girls/guys]?”

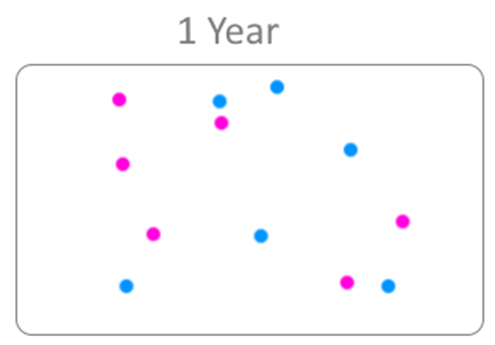

The first year, the discussion was interesting, instructive, healthy, and productive. It was like a few dozen darts were thrown at a wall of teenage struggles. If a wall could represent the range of challenges and struggles a teenager might mention, the year-one issues pinned to that hypothetical wall like the graphic below (pink for girls, blue for boys):

Seemingly random.

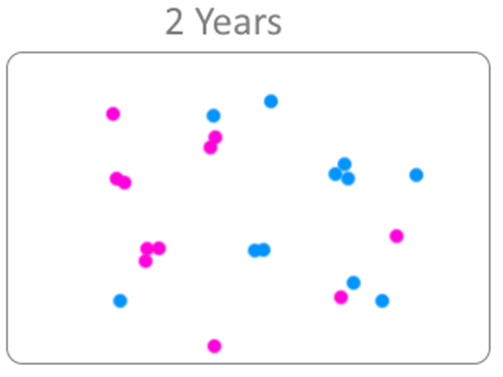

The following year, a few more hypothetical darts hit new locations on the same hypothetical wall, but some darts landed on and around the same issues as the previous year. Notable and interesting. The year-1 and year-2 metaphorical dart pattern on the wall might have looked something like this:

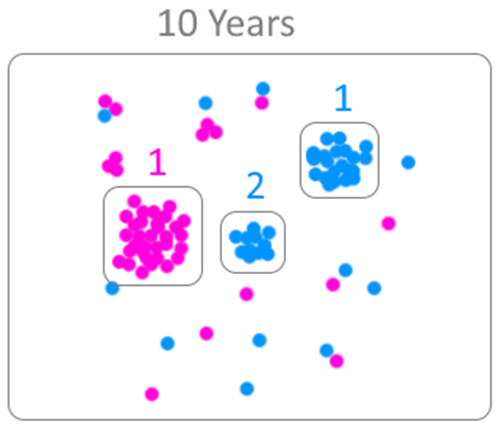

In subsequent years, a smattering of darts landed on the same wall. Over time, it became clear that certain struggles attract these conversational darts like magnets, predictably.

After a decade, I had sufficient ancillary data to be confident that subsequent conversations like these will result in similar discussions surrounding certain focal points because the darts on the wall started to group like this:

Certain internal, personal struggles seem shared among modern youth consistently across time.

Although the personality mix and overall vibe of each group differed considerably from year-to-year, the answers to these questions were surprisingly consistent, on certain points, just phrased differently.

So, what are these points?

For both girls and guys, there’s a definite #1 issue that tops the list every year (and a strong secondary issue for the guys) and then a smattering of other answers that are less consistent across time.

The “other” answers varied from year-to-year. Consequently, I’m going to focus my thoughts here on the top three issues I have identified that are consistent across time. Perhaps you see these same struggles in your own kids, or in their peers, or in your neighborhood and schools. Maybe, you feel them yourself as a young person, or even as an adult.

With that, let’s discuss the top issue for the guys, then the top issue for the girls, then the secondary issue for the guys.

Disclaimer: This is just soft, ancillary data assimilated by me from listening to a lot of students across a lot of years. It is by no means statistically significant nor rigorous in analysis, just observational. I also recognize these views are likely skewed and unique to the social-economic circumstances of the students I interacted with, primarily from upper middle-class families in suburbia. OK, on to my observations…

The Most Common Struggle for Guys

High school guys most frequently mention “living up to the expectation of my parents (especially my father), family, teachers, coaches, peers, and community” as one of their most significant burdens.

Let’s discuss.

Many parents, fathers especially, attempt to re-live their youth vicariously through their boys. All the heroic sports moments they never achieved are wished upon their sons. All the weight of unfulfilled academic ambitions from their youth are thrust down a generation in hopes it will accelerate future career successes greater than their own, even at the expense of the kid’s childhood.

“Why can’t they just see it?” asks the father, forgetting that he himself also enjoyed a bit of random-life-wandering and general knuckle-headedness at the same age. Truth be told, the father needed the life-wandering moments and the related downtimes and detours they provided.

Finding one’s way in the world necessitates some amount of exploration.

And exploration is ripe with the possibility of dead ends and retracing of steps.

Having forgotten the beautiful wonderment of youth afforded him through his early years of exploration and adventure (and perhaps a few misadventures as well), the father now projects his current deficiencies, regrets, and ultimate aspirations onto his son.

Why did I waste so much time, the father asks himself now, forgetting those parts were often called “fun” in his own youth.

In what is perhaps a sincere attempt to help the son avoid the same lack of progress, accomplishment or meaning, the father places undue pressure on his son to perform, in every way possible, to the highest possible standard, at all times.

Team and individual sports require excellence. Academic performance is a given. School clubs – top notch commitment expected. Consequently, there’s not an abundance of places and spaces to just chill. It’s all out, 100% on everything, all the time.

Everything the kid sets his hand to is expected to result in an exemplary performance. The pressure is simply too much, often because the youth of today are never allowed to coast, or fail, or come in second place. It’s simply unacceptable, and clearly a sign the son didn’t prepare or practice hard enough beforehand, according to the father, who is not shy to voice it.

Continuous exposure to high-performance culture places immense pressure on young men to perform and to validate their self-worth through the approval of authority figures in their lives.

Too many parents push for outcomes beyond realistic expectations, often robbing children of their childhood and converting their adolescence to a grueling level of work and a lack of proper rest.

This is unhealthy, primarily because the delivery of the supposed motivation often assumes the form of criticism and condemnation. The truth is,

Most young men do not find harsh criticism motivational.

To the contrary, they instead discover further evidence of their own shortcomings and failures, as they disappoint their fathers, once again, denoted by his tone of voice. This can significantly diminish self-esteem in young men.

I’m not suggesting that all young men experience this, nor that all fathers exude this type of performance pressure. But this was the most frequent issue brought up amongst young men each year when I talked with them. I’m also not suggesting that young women don’t experience the same pressure. They surely do. It just didn’t top their list in our discussions as it did for the young men. The girls had a different item at the top of their list.

A Common Struggle for Girls

High school girls most frequently mentioned “being objectified” as a significant struggle.

In a sense, this is rooted in the same fundamental issue voiced by the guys, in that it’s embedded in expectations.

It’s healthy for boys to hear a group of girls collectively articulate concepts like the following (paraphrased):

“When guys joke around about girls in a sexual way, we understand that you view it as ‘locker room humor’, but to us, it can be hurtful, as we tend to internalize these comments as a component of how we view and understand ourselves.”

This isn’t only aimed at guys. Being objectified is also sourced from girls. Girls notice girls. Girls talk about girls. Not always in edifying tones. It’s nuanced and disguised in the “Did you see what she was wearing?” type of comments. Sometimes, it’s just a facial expression in passing that speaks louder than words.

Sometimes, objectification comes in the form of telling girls what NOT to wear, preaching to them about their lack of modestly and their over-sexualized appearance.

When a teenage girl is told she is dressed inappropriately because her clothes do not sufficiently cover certain body parts, she must understand this to mean, “If this part of my body is uncovered, I should feel some form of shame.”

The next logical thought progression is, “There must be something about my body (these parts in particular) that is shameful.” This is a reasonable, logical conclusion, and one that many young girls internalize – that there is some amount of shame embedded within her very nature of being. This is not a healthy thought.

Rather than teaching her she is “beautifully and wonderfully made”, she is made to believe that she, or at least certain parts of her, are worthy of shame, and thus must be covered. Yet,

Physical modesty is derived from cultural norms rather than moral absolutes.

In the Western world, this cultural phenomenon traces all the way back to The Garden – where sin and shame must be covered. It’s understandable then, even if subconsciously, if someone concludes the reverse logic might also hold true – those things that must be covered must therefore be shameful. This notion is baked so deeply within the collective Western psyche, the thought progression and its natural conclusion are unavoidable, even if the logic is fallible.

It takes a powerfully confident person to defy cultural norms and be less affected by this pervasive thought that permeates our culture about women and how they perceive themselves based on what they are told they should NOT wear.

Doses of extreme counter-culture confidence are not often found in abundance in teenage girls.

Even if the shame is a false narrative, we still tend to want to cover it.4

Back to the boys.

A Secondary Issue for Boys

A secondary issue for the guys is a bit difficult to articulate, so I was impressed when high school students were able to succinctly get this concept across tactfully. In their words, it sounds something like this:

Guys do not feel fully appreciated for the weight of responsibility they feel they must bear for being a man.

Manhood has certain societal expectations and obligations that males, rightly or wrongly, feel they must carry. At the lowest, most innocuous level, there is some holdover idea that a gentleman opens doors, pays for dates, and similar. Likewise, men are by default assigned the task of ridding the house of spiders, rodents, and possible threats from intruders. There’s also generally an expectation that men should perform the more physically demanding tasks (mowing the yard, fixing the car, and many of the modern-day equivalents of plowing the field, often tasks that require more physical strength).5

At a higher level, there is a general societal expectation that the man is the designated protector of the family. When something goes bump in the night, the man is often volunteered as the first responder, whether he likes it or not.6

Higher still resides a societal expectation that the man will provide for his family, especially financially.7 This translates into a seriousness about the direction your career might need to take and the number of hours you might have to commit to perform this function satisfactorily.8

At an even higher level, there is still a societal expectation that men will be the last off a sinking ship or be required to fight wars in foreign lands. I understand women are entering the armed forces in greater numbers, so please don’t take my statements to the extreme and twist them into something I am not saying. I am simply reporting back what the teenage guys have been voicing. This is a real concern for them. It is not, by any means, a claim of unfairness. Rather, it’s a description of a sentiment, as best they can articulate, that

the weight men feel they must carry is underappreciated9

And this seems to be the heart of the matter. The young men are willing to take on these tacit obligations, but it can be demoralizing if underappreciated or shamed by being labeled as toxic.

No one likes to feel unappreciated.

Clearly, there are many things women are expected to do based on societal pressures for which they are also underappreciated. Don’t hear me say something I’m not saying. It’s just that the guys articulated this en masse, and the girls did not (not collectively). I’m just summarizing what I heard.

Conclusion

What might we conclude from this? Maybe that’s an exercise for you to help me with in the comments, but I’ll make a few remarks.

- Simply airing these thoughts to each other (guys and girls) is revelatory and helpful to both parties.

- We could go a long way by simply better appreciating and edifying each other, especially in our youth.

- We are not inventing new emotions. While technology has changed, communications have changed, and channels of interactions have changed, people still fundamentally struggle with the same emotional challenges at their core across time.

- The key issues discussed, for both guys and girls, are rooted in the same notion – a lack of understanding that they are enough, just as they are10 …even though they could be and perhaps will want to be more, with time.

I am curious if these items resonate with what you are seeing in your households, your schools, your neighborhoods, yourself. Use the comments section below to add to the conversation.

Related Posts:

The Danger of Normalizing Extremes

Practical Advice On Budgeting & Spending

Opposing Forces – Growth from Difficulty

A Framework to Help Develop Your Criteria for a Spouse

Follow Past Midway if you would like an email notification of new posts.

FOOTNOTES:

- At least for the socio-economic demographic of students flowing through my purview.

- Sometimes students feel more comfortable sharing with a mentor rather than their parent(s), especially if the subject matter involves an issue the young person thinks might provoke disappointment, disapproval, or undue concern from parents.

- Sometimes it’s best just to ask directly.

- This is a beast of a footnote. I dropped it from the main body because it sounded a little preachy, at least it reads that way to me… and I wrote it. I was inclined to delete it completely (and may still). Feel free to skip this footnote and move on to the second issue for the boys.

Cultural Norms vs Morality

Collectively, we tend to conflate cultural norms (that which is culturally appropriate), with moral uprightness.

In judging how covered a girl is, we miscommunicate to her that she has breached some moral boundary, when, in fact, she has likely only breached a cultural boundary. Breaching a cultural boundary is also important to understand. I’m not advocating that we completely ignore cultural norms, but it is a different thing entirely from breaching a moral boundary.

So, what’s the difference?

Cultural boundaries drift from one location to another and even ebb and flow through time. Certainly, it is wise, even polite, to respect the cultural limits of attire and behavior for the location, culture, and period we are in. To do otherwise would be considered disrespectful to that culture, to those around us.

Some clothing attire considered “normal” and culturally acceptable to wear in public in Europe would likely draw attention in the U.S., particularly when comparing what is worn at the beach.

Accepted attire also differs across time.

Not too long ago, in the Western world, it would have been taboo for a woman to show her ankles in public. We are not so many generations from this view (just three generations for me). Meanwhile, Gen Z seems quite comfortable with a thong-style swimsuit at the beach, and sometimes at the local suburban neighborhood pool. This is much to the chagrin of older generations, who also pushed the limits of what their parents and grandparents thought acceptable, by wearing pants, then shorts. Gasp! What’s the world coming to?

So, there are generational differences, and this is fine. Cultural norms are fluid over time. And, it makes sense, to a certain extent, to adapt to cultural norms for the time in which you live. (I feel like there should be lots of caveats here on this point… but forgive me if a glance over this for the sake of brevity. I think you get what I am trying to convey here.)

I am a proponent of people who nudge arbitrary cultural boundaries, without trespassing moral boundaries. If no one were pushing cultural boundaries, women still wouldn’t show their ankles in public and would still wear long dresses, even in the Texas Summer heat while working outside.

The southern state’s climates are way too hot and humid to continue wearing what men and women used to wear, especially while performing manual labor outside. I have no idea how previous generations managed the heat in their allotted, culturally appropriate attire for the time (without air conditioning!).

Judging

The most obvious thought here is that we should not make a judgment about others, at all. This is also incorrect and potentially unsafe.

It’s important to render judgements, especially first impressions. If you see someone approaching you in a dark alley, you can be sure you make a quick judgment about that person… and you should. In incidents like this, judgement is the skill that keeps you alive and unharmed.

We can’t say “Don’t judge,” and simultaneously say “Use your judgement”.

So, we might then say, “Fine. Judge, but don’t share your judgement with others.” Well, not so fast…

Continuing the same example, if you make a “potential danger” judgement about someone in a dark alley, your friends definitely benefit from you sharing this insight. This also keeps them alive and unharmed.

Here’s a less severe case. If you judge someone as emotionally toxic, your friends probably also need to know this data point. So, we should both judge and perhaps discuss our judging thoughts with those close to us.

But there’s a key difference between judging (the act of making judgments) and being judgmental.

Good judgement comes from wisdom rooted in experience.

Being judgmental assigns a morality rank or deficiency to another.

In the case of what a girl wears, discussed above, we need to be careful that we do not confuse a cultural fashion choice with amoral behavior.

Judgment = I do not like that fashion choice. It seems culturally inappropriate.

Judgmental = she is over sexualized and likely promiscuous.

Through judgment, we become aware of social norms for the time and place. Communicating judgment socializes norms across the local population and can let someone know if their attire is outside normal for the place, time or venue. By contrast,

Judgmental comments condemn a person for who they are.

A girl can change her clothes if she wants. She cannot (as easily) change how she was made or how she now perceives herself and her self-worth.

The point here is that we sometimes assign an absolute morality claim to a cultural norm. But we should not assume that our cultural norms hold some type of global, infinite moral standing. They often do not.

- I feel like I might get jumped on for sounding sexist here… please don’t take it that way. These are certainly broad sweeping statements. There are exceptions, I know. But for the most part, historically, men performed the more strenuous tasks that required brute strength. Don’t hate on me.

- Trust me, we don’t like it.

One night, there was a noise in the basement in our first house in a not-so-great neighborhood. It was 2am. The area of town lent itself naturally to the fear of a break-in. So, I grabbed my wooden stick that I kept under the bed. The previous owner had left it in the basement. I reckoned it was the only “weapon” I had in the house because it also had a large nail in the end… and had a good grip.

I walked downstairs, fearing what might be behind each door as I opened it. I thoroughly checked every dark spot and closet. Five minutes of agony, mostly delaying the idea that I would eventually end up inspecting the dark basement.

I took a deep breath, firmed my grip on the wooden instrument of defense, and began my walk downstairs into the basement. I did not turn on the light. I knew my basement better than an intruder. I reasoned darkness was my advantage. This is a high-adrenaline state of mind. Then the cat moved in front of me. This was the adrenaline spike, the climax in emotion, but also the great relief that our burglar was in fact the cat doing what cats do in the dark hours of the night… rummaging around, probably chasing a mouse, fulfilling his duties and overall job description.

My point here is… I was the one walking around in my underwear brandishing a long stick with a nail in it, ready to defend the family and property. I think it would be difficult to argue against the notion that, at least traditionally, and therefore culturally, these are the generally acceptable assigned roles in circumstances like this. This is a job most wives assign and expect of their husband. And with that, we carry the weight of it. Just an example.

- Less and less so with each new decade… but the residual sentiment still hangs in the air for many men to breathe.

- I’m not judging the merits of the point, simply that it has been communicated to me that there is this inherent pressure felt by the high school guys on this front.

- The point is to simply communicate what I have heard from the guys over the years without judgement to its accuracy.

- Credit: Mr. Rogers.

Thanks! Your observation on the male struggles are valuable to be said and fascinating to read. It is something I knew in the back of my mind that young men struggle with but it being presented specifically like this makes the issue clear. Also bringing to life self destructive behaviors in men is so important for the readers to relate to something since I think this is something everyone can relate to yet not many talk about. I’ve known several men who act on self destructive behaviors due to societal or peer pressure about just what it takes to be an adult man.

The take on younger women was an interesting read and how drastically different the issues are compared to young men. It’s interesting because objectification can be seen as a superficial issue (no pun intended) and not necessarily taken as seriously as an issue such as the young men not feeling like they are good enough. However, the issue of objectification roots deep.

It’s an interesting read and I love that you have taken the time to write your observations and thoughts after years of listening and to “separate the patterns and signals from noise”.

You asked about our own observations and I would say that, as you mentioned, the groups that we work with definitely influence the observations. And if I were looking for patterns, they might not be the same. But, mine were not group discussions, they were more individual, and therefore very specific struggles. I also tended to work with a very different socioeconomic class and very, very intelligent youth, often on the spectrum. So, I do believe that the things I would’ve pulled out as my top issues were different, but I think they were very child specific rather than general population specific. And I would have to write my own blog for that! 😉

I very much appreciated your long footnote. I honestly think you could’ve broken this blog into three blogs. Boys. Girls. And one about cultural norms, morality, judgment, and being judgmental. I would very much enjoy a longer blog on the third topic.

I also think you’re insights into Boys was better and more descriptive than the section on girls. I think this is probably because you are male. You can relate and give examples like you did in your footnote. What you said girls number one problem is, is definitely true, I believe, but I think it goes so much deeper than that. It’s a very complex and nuanced topic that deserves more than what was written here.

Something I find interesting, as it relates to your point about cultural norms changing over time, is that I feel these issues for both boys and girls are strongly related to the fact that gender identity is changing. As women have entered the workforce, been able to wear pants (ha), have bank accounts, own land, be able to mow the lawn, etc. We as a culture, are trying to understand what the new gender norms are. As that happens, I think we see more pressure on the old gender norms, which I would sum up as: Beauty for women. Strength for men. Which ties neatly into your 3 issues. It will be interesting to see how this plays out over the next several generations.

Sorry for the long reply. I have a million other thoughts, but that speaks to a very interesting and provocative blog.

Thanks as always for sharing your insights and putting yourself out there.

Christy – thank you for your thorough comment. I appreciate it. And you are correct, I did not go into as much detail on the girls section precisely because I am less knowledgeable on this topic… because I am a male, as you mentioned, but also because I have spent considerably more time with the guys and therefore have more conversations and data points from them. Thanks for reading.

This is a great framing of the issues that are felt by this age of student in the respective demographic. I feel as though these sentiments are usually trivialized or misunderstood by those older than high school age, but i felt that your synopsis here was a good representation.

I’m interested in how you gathered your data here. Did you ask the same set of questions to classes of high schoolers of a set of years?

Curious to how you came upon these topics as being the most common within the demographic.

David – thanks for reading and for your comment. There was nothing rigorous about the data gathering for this, but I did generally ask the same open-ended questions from year-to-year (I had the questions printed out). As for the three thematic topics I narrowed for this blog, these just seemed more recurring than any other issues mentioned.

Came across your blog post today. While I don’t mentor many young women, I spend quite a bit of time mentoring Freshman and Sophomore college students at my alma mater, Auburn University.

I quite resonate with your takeaways for young men. Expectations are by far in a way the largest pain point that consistently comes up in my conversations over the years.

Thanks for putting pen to paper on the subject. I appreciate the perspective.